A risky assignment

How opportunity, diplomatic skill, and luck helped New Zealand play a role in resolving conflict in Bougainville.

In early July 1997, a New Zealand Defence Force C-130 Hercules aircraft landed on a dusty coral airstrip in the town of Buka in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea.

The plane was carrying a group of Defence Force personnel and Bede Corry, the Private Secretary to New Zealand Foreign Minister Don McKinnon. Bougainville had been in the grip of a devastating civil war between those who wanted independence for Bougainville and those loyal to the Government of Papua New Guinea. The risks to people visiting the island were high, and the Defence Force immediately began setting up a command post adjacent to the C-130.

Bede was there to help pick up Bougainville Transitional Government representatives from the north for peace talks that New Zealand was scheduled to host the following week. John Hayes, New Zealand’s former High Commissioner to Papua New Guinea, and John Mataira from the High Commission had gone to Bougainville for the same purpose. They had been travelling around the main island by helicopter, to pick up representatives from the Bougainville Interim Government and its 'Revolutionary Army'. The two groups being collected by Bede and John were the parties to the civil war.

Bougainville’s steep terrain and dense jungle make movement challenging at the best of times. The difficulty in collecting the delegates had been compounded by close to a decade of bitter fighting between those who wanted independence and those loyal to the Government.

Travelling in person to collect the delegates was a major logistical exercise but it was also, in some senses, a powerful signal to the Bougainville factions of New Zealand’s willingness to support a peace process: the New Zealand diplomats’ presence was to show good faith to the delegates by raising the stakes for anyone who wanted to attack them as they left. Previous peace process had been de-railed by violent ambushes against the participants. And the full extent of this risk was about to become apparent.

While the New Zealand Defence Force established a perimeter around the aircraft, Bede went to the edge of the runway in search of Mr Hayes.

He soon found some Papua New Guinean soldiers who directed him into the jungle where Mr Hayes was sitting in a semi-circle with members of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army he had accompanied by helicopter from the south. The conversation was strained and Bede later discovered why: while Mr Hayes had been in the air, the chopper carrying him had been hit by gunfire, badly damaged and forced to make an emergency landing.

No one was seriously hurt, but some representatives were now worried the talks would be cancelled.They were right to be worried. Either party could have chosen to walk away in the face of such an outrage and, if there had been loss of life, New Zealand would have had to question its role in the peace process.

As it transpired, the shooting ended up having the opposite effect. All parties were struck that an outsider, a New Zealander, had been willing to risk his life in an effort to bring them together. This sent a powerful message and helped commit the leadership of both sides to the peace talks.

Mr Hayes was adamant too – everything was fine, and the talks were still on. As he later said: "I’d invested too much damned effort into getting this thing sorted and I wasn’t going to be derailed. Besides, that gave me plenty of moral authority … intimidating them with integrity. You’ve shot at me, we’re all in this together, and we’re going to get it sorted.”

The people of Bougainville would ultimately be responsible for bringing an end to the conflict which had ravaged their island for so long. A number of countries, groups and individuals, would have a role.

But New Zealand politicians, diplomats, and military and police personnel would play an instrumental part. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s role was characterised by careful and skilled diplomacy, but also moments of risk, luck and opportunity.

At its heart, it is a story about New Zealand’s place in the Pacific, the way we work with our neighbours, and the values which underpin our diplomatic effort.

Background image: An aerial view of a settlement devastated by conflict on Bougainville.

The seeds of conflict

Bougainville was declared part of a newly independent Papua New Guinea in 1975. Prior to this Bougainville had been, at various junctures, under German, British, Japanese and Australian control. In addition, Bougainville’s close ethnic ties and proximity to the Solomon Islands did not gel easily with being part of Papua New Guinea.

Discontent was brought to a head in 1988 by a long-running dispute over the uneven economic returns and environmental impacts from Panguna copper mine. The mine, located in Bougainville, was centrally important to Papua New Guinea, providing over 45% of the country's national export revenue.

Under the leadership of a former mine worker, Francis Ona, disaffected Bougainville people ran a sabotage campaign which led to the closure of the mine in 1989.

The Papua New Guinea Government responded by sending Police and later Defence Force personnel to restore law and order. These measures, and allegations of indiscriminate use of violence against civilian populations, fuelled more anger in Bougainville.

Francis Ona declared Bougainville independent from Papua New Guinea, and formed the Bougainville Interim Government. A period of conflict waged by the Papua New Guinea Defence Force and the newly formed Bougainville Revolutionary Army followed.

In early 1990, the Papua New Guinea Government enforced a total blockade of Bougainville. The blockade, which lasted until 1998, meant the people of Bougainville had no access to medical services. Men, women, and children died of preventable diseases such as malaria, tens of thousands of people were forced into refugee camps known as ‘care centres’. Some estimates put the death toll, including from preventable illness, at 10,000.

Not all Bougainvilleans supported Francis Ona or the calls for independence. In northern Bougainville clans established the Bougainville Transitional Government in 1995, which was supportive of Papua New Guinea rule. Its military wing, the Bougainville Resistance Force, drew support (logistics and weapons) from the Papua New Guinea Defence Force.

In the law and order vacuum, a cycle of violence began that pitted families, clans, and individuals against one another. Numerous attempts to bring parties together failed, including two short-lived ceasefire agreements in 1990 and 1991 that neither side honoured.

Background image: Panguna mine, Bougainville, in shut down. Photo: Alex Smailes

New Zealand's drivers to get involved

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, New Zealand’s High Commission in Papua New Guinea and other missions in the Pacific had been following developments with concern.

New Zealand diplomats had made regular visits to Bougainville to encourage the sizeable New Zealand population to leave the island in the face of a deteriorating security situation. These visits helped to build relationships with people in Bougainville who later became critical to the peace process.

Over a number of years New Zealand’s High Commission in Port Moresby worked to establish links and networks with the people of Bougainville, while not putting the Government of Papua New Guinea offside, and to lay the groundwork behind New Zealand’s subsequent involvement. This relationship and trust building was critical in ensuring that New Zealand would later be seen by both sides as a credible and respected partner in the peace process.

This early involvement wasn’t perfect; mistakes were made and learned from, but over time the personal integrity, commitment, and occasionally the bravery, of New Zealand’s diplomatic staff working in Port Moresby helped build the conditions required to start seriously working towards peace.

In the late 1990s, New Zealand's Foreign Minister Sir Don McKinnon travelled to Bougainville at the invitation of Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Sir Julius Chan. What he saw convinced him that New Zealand should offer to help.

“(It) was a real shock to me – because you didn’t see anybody when we arrived at Arawa [Bougainville’s largest town], and then suddenly people started coming out of the bush… and they were not healthy looking people. They had clearly been suffering, they had clearly not had the kind of food they were used to, and it was all a pretty miserable and somewhat of a heart-wrenching sight. I left there thinking, “We’ve got to do something. This has been going on a long time… That’s when I brought the Foreign Affairs officials into my office and said, 'Look – I want some really big ideas here… this is in our home region, and it just shouldn’t be happening.'???

In Wellington, a small team gathered to plan New Zealand’s engagement with both Papua New Guinea and the Bougainville factions. This group included Bede Corry; John Hayes; Neil Walter, a Deputy Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and Roger Mortlock, Chief of Operations of the Defence Force.

Neil Walter recalls: "We were fortunate to have a group of people at the time who did have on-the-ground experience in Papua New Guinea and Bougainville. John Hayes was well known to the people of Bougainville, and Papua New Guineans generally, and trusted by them. … Bede Corry, who was gifted with a great sense of political realism ... and he could liaise and work well between Don McKinnon and the others involved in the process. Gordon Shroff, our ranking expert in Pacific affairs – and several other people both in Wellington who had had some experience around the Pacific. And that general experience you get in a diplomatic career of understanding other cultures, other systems of government, and being able to respond to a negotiating situation once you are thrown into that."

Around the same time New Zealand was considering how to help, the Papua New Guinea Government, led by Sir Julius Chan, was about to make a further and more radical attempt to end the conflict. The Chan government hired a UK security firm called Sandline International to act as ‘advisors’ in Bougainville. But the move backfired: the use of foreign mercenaries did not sit well with the Papua New Guinea Defence Force leadership.

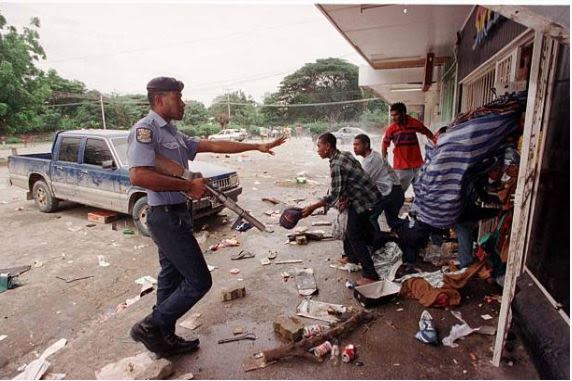

Armed police stop men exiting a damaged shop.

Looting near the Murray Barrcks, Papua New Guinea, during protests against Sandline. Photo: Alex Smailes

The Papua New Guinea Defence Force launched a secret operation ‘Rausim Kwik’ (get rid of them fast), to expel Sandline from Papua New Guinea. When news of the Sandline affair became public, it was a major political embarrassment for the Papua New Guinea government. There were protests and even rioting in Port Moresby and the Sandline contract was cancelled.

The fallout forced political change and drew international attention to Bougainville.

Gathering momentum

The politics in Papua New Guinea now shifted quickly. The timing was right for New Zealand to play a key role in resolving the conflict.

Bede explains the critical role that Mr Hayes played in getting Papua New Guinea's support: “He has great mana with generations of Papua New Guinea political leadership… John also had great standing on Bougainville. He had knowledge, he had connections, he had mana, he had courage. And he had a phrase he would keep using: intimidate with integrity. We will continue to do the right thing by you, Papua New Guinea and Bougainville. We’ll intimidate you with our integrity; we’re not going to be blown off course, we’re not going to get into scraps, we’re not going to get into minor disputes about things that don’t really matter. We’ll stick by our word, and we’ll do what we said we were going to do. He was absolutely indispensable.”

Mr Hayes travelled to Papua New Guinea without a concrete plan in mind, but he knew the value of relationships, particularly in the Pacific context. “I went sailing, and I went fishing, and I wandered out along on my own, and I saw everybody I could among the Papua New Guinea establishment, to try to feel out the way forward.”

He ended up having a conversation with Sir Julius Chan that lasted some hours during which it became clear that Papua New Guinea wanted to make peace, and New Zealand had an opening.

By this point, dynamics in Bougainville were also shifting. The parties, wearied by fighting, were looking for their own way to end the conflict. The hard-line Bougainville Interim Government President Francis Ona was sidelined and the more conciliatory Joseph Kabui, later the first President of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, moved to the fore.

Mr Kabui later wrote: “We realised at the time there must be unity. The Bougainville Revolutionary Army had become well aware of their mistakes, particularly after the 1990 ceasefire when the Bougainville Revolutionary Army brought about anarchy, and as a consequence of that we people, who had been united at one time, were now divided and were now fighting one another.” 1

Overseas, a network of Bougainville expats had been seeking to raise the profile of Bougainville’s situation in Europe, Australia and Solomon Islands.

Bede: “Having decided that (we) wanted a peace process to be investigated, we were left with the question of how the hell do we do that? Bougainville was subject to a blockade, it was cut off from the outside world. Nobody came, nobody went. We knew really of one Bougainvillean of any stature outside of Bougainville. He was a man called Martin Miriori, who was a leader of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army in exile… We decided, knowing very little about Martin - whether he was a credible figure, whether he was a suitable vehicle - that we didn’t have too many options but to go through Martin.

Under a cloak of considerable secrecy we brought Martin to New Zealand and there was a meeting in Auckland between Martin Miriori, Don McKinnon, Neil Walter, John Hayes and myself at the old Novotel down on the waterfront. The essential message was: Martin, if you can get a message to your people that we are willing to help, then we would be very pleased for you to do that. Martin said 'Well, it’s funny you should say that because, for the first time in years, the two Bougainvillean factions, the Bougainville Revolutionary Army and the Bougainville Transitional Government, are talking about having a reconciliation meeting and we don’t know where to do it'."

With Papua New Guinea’s agreement and informal contact established between the parties to the conflict on Bougainville, New Zealand’s role now move to a more formal phase. Burnham Army Camp outside of Christchurch was identified as a suitable location for peace talks but both parties wanted to send significant numbers of people. On the eve of travelling to Bougainville with John Hayes to gather delegates, Bede had a stark reminder of the risks involved.

“An emergency meeting was held in the Ministry with other stakeholders – principally the New Zealand Defence Force and the intelligence agencies. Some of the risks became quite apparent, to the extent that the last words I remember from that meeting were from a very senior Ministry official at the time, describing the operation as verging on the foolhardy.”

Despite the risks and setbacks, including the attack on John’s helicopter, around 70 delegates were eventually flown to Christchurch in late July 1997.

1. Joseph Kabui, "Reconciliation A Priori", Peace on Bougainville Truce Monitoring Group, edited by Rebecca Adams, Victoria University Press, 2001.

Background image: Bougainville from the view of a helicopter

The Melanesian way meets the New Zealand way

Formal peace negotiations are usually tightly structured affairs. They typically involve only the leaders of the armed groups, with external facilitators allowing only a few days for negotiation, followed by political pressure to induce truces or peace agreements. For the Burnham talks to succeed, a different approach was required.

Many participants felt that previous attempts had not allowed adequate time to fully address the issues. New Zealand’s own values and culture, importantly tikanga Māori, also shaped how the peace process in Burnham was structured.

Bede explains: “[W]hen the Bougainville factions arrived on a very cold morning in July 1997, the first thing that happened to them was a pōwhiri, led by the soldiers of the camp. You could see this almost transformative effect on the participants as they realised there was something about New Zealand that they hadn’t appreciated – that they were being welcomed in a way that, while it had limited cultural familiarity to them, nonetheless said New Zealand was of the Pacific and was a different kind of place than they might have expected. That’s something of which they continually spoke – the effect of that pōwhiri."

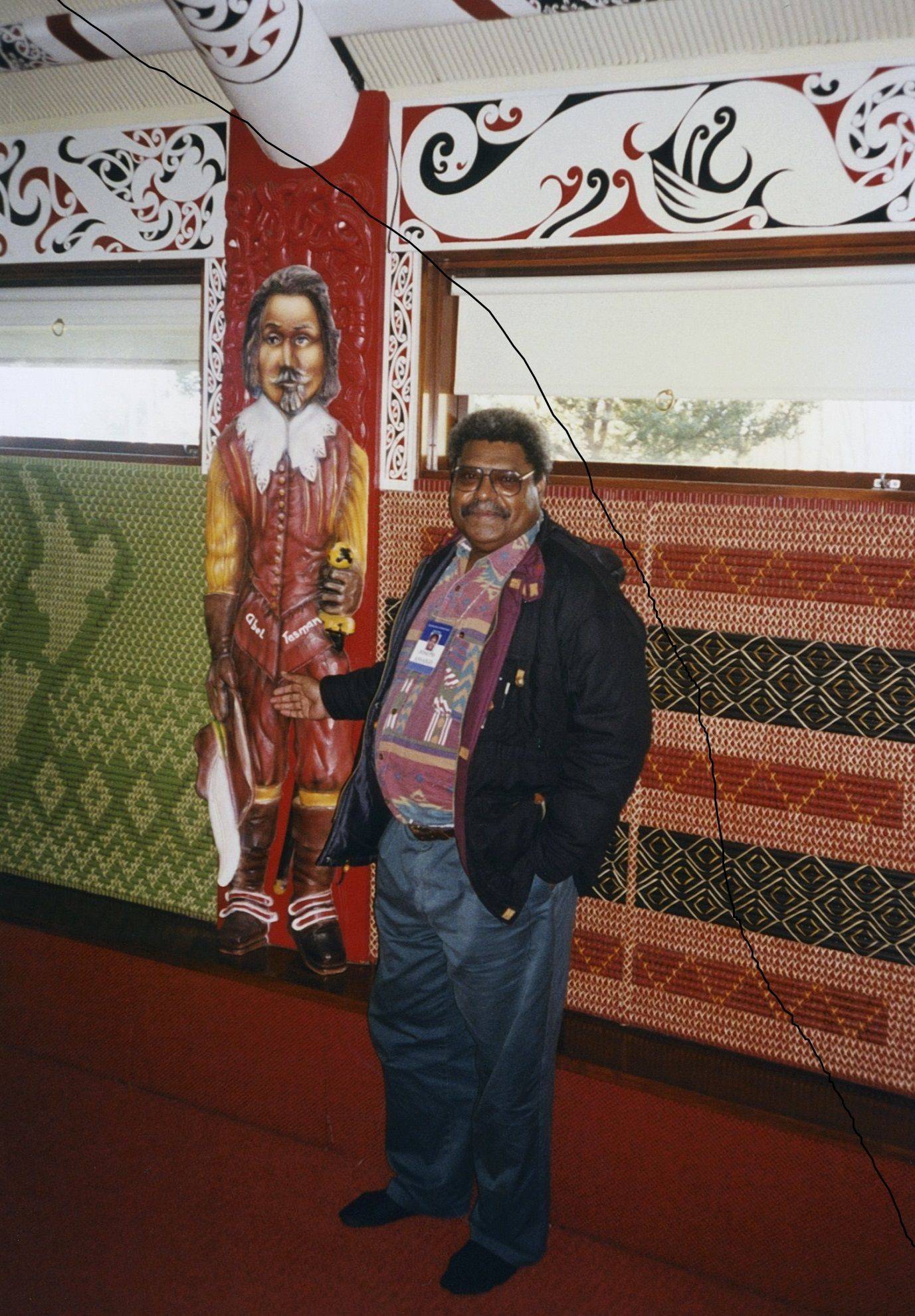

In fact, Māori culture had been helping to build trust in Bougainville and Papua New Guinea for the decades leading up to Burnham and shaped how New Zealand was seen in the Pacific.

John Hayes had recognised the value in this during his time in Papua New Guinea. “When I went to villages, I would always kick off in Māori – Tihei Mauri Ora, like if I was going to a marae here. And then I would speak in pidgin, and then we would sing a waiata… It was about establishing our Kiwi brand – our New Zealand brand – in a way that was actually quite Pacific – or certainly of the Pacific.”

Bougainvillean cultural practices were also rightly given prominence in the talks.

Parts of Bougainville, especially around Panguna, are matrilineal, and women are regarded as ‘mothers of the land’. Women leaders from different parts of Bougainville were among those who came to New Zealand to join the peace process. Even as their physical safety and living standards had been shattered through the conflict, their moral authority had been enhanced through brave efforts to stop some of the worst violence, and to reach out across dividing factions to call for reconciliation. Their participation had a profound influence on the peace process.

The second cultural practice incorporated was the ‘taraut’. Literally this translates as ‘vomit or remove’ and describes a cathartic practice where participants voice every painful thought and feeling to the entire group. These were long, large, and uncomfortably intense meetings. New Zealand Defence Force officials had to position themselves between enemies and occasionally restrain individuals.

As John Hayes explains: "We stayed out of the meetings. ... [The approach] was to say this is your process, you have to find your solution, your outcomes – it's not for us to tell you what it is, but whatever you decide to you want to do, we’ll work with you.”

New Zealand was careful not to impose solutions or time limits on the Burnham talks, despite their considerable cost. As a result, the talks had no set agenda and took two weeks. The wait was worthwhile: the talks produced the Burnham Declaration of 18 July 1997, which included a ceasefire and the withdrawal of the Papua New Guinea Defence Force from Bougainville, and was a vital step towards peace.

The prisoner exchange at Kangu Beach

The success of the first round of Burnham talks was cause for celebration, but it presented a new challenge: returning the delegates to Bougainville.

The delegation were delivered to Honiara in Solomon Islands by the New Zealand Air Force. New Zealand then provided the naval vessel HMNZS Canterbury to transport them back to Bougainville, along with some of the Bougainville refugees who had been living in Solomon Islands during the conflict. On arrival in Honiara, the vessel was inundated with people who were eager to return to their home now a truce was in place - a reminder of the heavy toll the conflict had taken on the civilian population.

The vessel set sail for Bougainville with a small number of the refugees, the delegates, security personnel, John Hayes, Bede Corry, and Rob Hitchings, the New Zealand Defence Force’s Deputy Director of Joint Operations, on-board.

They had another pressing task. Three Papua New Guinea Defence Force personnel and two Papua New Guinea police officers had been held captive for a number of years in southern Bougainville and used as a bargaining chip by the Bougainville Revolutionary Army. New Zealand had been able to get public agreement from the Bougainville Revolutionary Army that the hostages would be released, but only in the presence of a New Zealand official.

The Canterbury moored in the waters off southern Bougainville and the senior Papua New Guinea Defence Force Commander from the main encampment on Kangu Hill was brought aboard to reassure his soldiers that the vessel had come in peace.

Bede: “I remember going up to the bridge and asking him to speak to his men on the island. And it sent a shiver down my spine, as over the HF radio he said to his battalion – which was positioned on a hill sitting above where the frigate was moored – ‘This is your commander. Please hold your fire. We are here in peace.’ It was a spine-chilling message because it reminded us all of what could happen with this frigate sitting there like a sitting duck.”

It worked and HMNZS Canterbury was not fired upon, but efforts to contact the hostage-takers proved more difficult. They had not received word about the public undertakings given at Burnham and no one could raise them on the ship’s radio. Again Mr Hayes put his local knowledge and standing to good effect. Using his networks, particularly among church groups, he put out word that the hostages were to be released and went ashore himself with a small security detail.

Rob Hitchings remembers the prisoner exchange as a highlight of his involvement. "Going ashore with John Hayes, not knowing what was going to happen... and landing on a beach with nobody there. And then, over a period of time, seeing some 500 Bougainvilleans arrive.”

After protracted negotiations the five hostages were released into the care of the ship’s company and came on board the Canterbury.

Bede: “In the way of these things in Melanesia, as they left their captors [the former hostages] were given gifts – and those gifts included the most beautiful tropical parrots you’ve ever seen. So, in good nautical vein, there were also a few parrots aboard with the returning hostages as well.”

The release of the hostages had a major impact. Newly elected Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Bill Skate met them at the airport when they were returned to Port Moresby by a NZDF C130. This was an early win for the new Prime Minister and helped shift perceptions of the Bougainville situation in Port Moresby, as well as shining a favourable light on New Zealand’s involvement.

Image 1: The delegation going ashore.

Image 2: The HMNZS Canterbury moored off Bougainville.

Keeping the truce

The deployment of the Truce Monitoring Group for Bougainville was one of the primary outcomes of the Burnham Peace Talks.

From the outset, it was agreed that New Zealand would make up a substantial part of the group, including by playing the leadership role, and that Pacific Island country participation was critical, and ultimately it included civilian and military personnel from New Zealand, Australia, Vanuatu and Fiji.

The decision to keep the Truce Monitoring Group unarmed was widely remarked upon in the media and demonstrated to the parties of the conflict that they were responsible for ensuring the safety of the monitors.

On 20 November 1997, the first tranche of the Truce Monitoring Group departed for Bougainville from Christchurch. New Zealand Defence Force Brigadier Roger Mortlock, who led the Group, described the special nature of the Group to the New Zealand media who had assembled to see them off. “The Māori Concert Group”, he told reporters, “and a good shipment of guitars are going to be the main weapons in our arsenal.”

Over time, patrols established deep relationships and sometimes friendships in local villages. A medical facility brought in for the Truce Monitoring Group was extended to critically ill Bougainvilleans. Music and singing, sports competitions, shared food, and storytelling also deepened understanding between the Truce Monitoring Group and the local populations. This all helped to build confidence in the peace process among ordinary Bougainvilleans.

Brigadier (Rtd) Roger Mortlock explains the purpose of the Truce Monitoring Group: “The Truce Monitoring Group’s effort was directed at re-empowering the people to influence the men with guns to make the right decision. ... Taking the approach we did, one might argue was a high risk. But the circumstances of the people on Bougainville argued that that high risk was a worthy and honourable risk. We did something different; it worked. … To interact with a people that has given up any form of hope was sobering … There was a strong determination to get it right. I think any decent person would have.”

Image 1: Background image: New Zealand troops in the Truce Monitoring Group at their farewell ceremony in 2003.

Post-1997: Rebuilding Bougainville

In 1998 Don McKinnon convened a second summit in Christchurch and oversaw the negotiation of the Lincoln Agreement. This extended the truce to a permanent ceasefire and resulted in the creation of the Bougainville Reconciliation Government. A process for weapons disposal, the withdrawal of the Papua New Guinea Defence Force from Bougainville, and the granting of amnesties and pardons were also agreed.

Alongside the formal negotiations for a lasting peace, New Zealand recognised the need to deliver a tangible peace dividend to ordinary Bougainvilleans, helping to restore public services and economic activity. That resulted in an MFAT-staffed Bougainville Liaison Office in Arawa, and a programme of recovery and development activities on Bougainville, delivered in partnership with Oxfam New Zealand, VSA, the Bougainville Transitional Government and many local communities and organisations. It is a line of work which continues today.

In 2001, the Bougainville Peace Agreement was signed that brought an end to the crisis. It provides a roadmap to lasting peace and a political settlement for the people of Bougainville based on three pillars: autonomy, weapons disposal and a non-binding referendum on Bougainville’s political status.

New Zealand’s decision to give a voice to Bougainvillean women during the formal peace process has also had a lasting impact. It is widely cited as an example of international best practice in peacebuilding. It has echoes in contemporary Bougainville where, unusually for Melanesia, the small parliament of the Autonomous Bougainville Government has three reserved seats for women and currently includes four women MPs.

Ruby Miringka, who signed the Bougainville Peace Agreement as the representative for Bougainville women, leads an innovative health programme on the island with Leprosy Mission New Zealand, funded by the New Zealand Aid Programme. Other women leaders who took part in the peace process, including Sister Lorraine Garasu and Helen Hakena, continue to be important leaders of NGOs and community groups.

On the ground in Bougainville, the New Zealand Police work in partnership with the Bougainville Police Service to build capability around community policing. Like the Truce Monitoring Group, they are unarmed.

Seventeen years on from the signing of the peace agreement, New Zealand’s relationship with Bougainville and with Port Moresby is strongly coloured by positive memories of how New Zealand conducted itself during the conflict and peace process. Both sides continue to remind us that New Zealand played a key role and has an ongoing responsibility. This is becoming more tangible as the nominal date for the referendum on Bougainville’s status is set for mid-2019.

“I think MFAT deserves to be proud of their role. I think the Defence Department does, too. I think Don McKinnon does, too. I think the people of Bougainville do - I think the women do, and I think the Ministers do - but I think the people in general do.” Brigadier (Rtd) Roger Mortlock

Sir Don McKinnon talks about the lasting effects of the process that New Zealand contributed to: “The legacy is in what you see on the ground. We got peace – and that peace is now sustained for coming up for 20 years. We took a long time to get there. There were two Burnham talks, then there was the Lincoln talks, there was time up on Bougainville. But it was a case of walking alongside the Bougainvillians. We weren’t striding out in front saying 'follow me'; we weren’t pushing them from behind.”