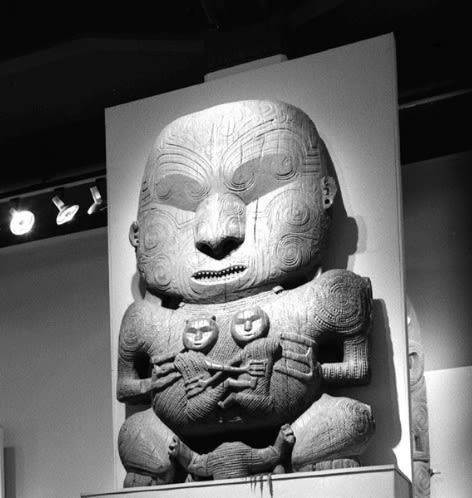

Te Māori

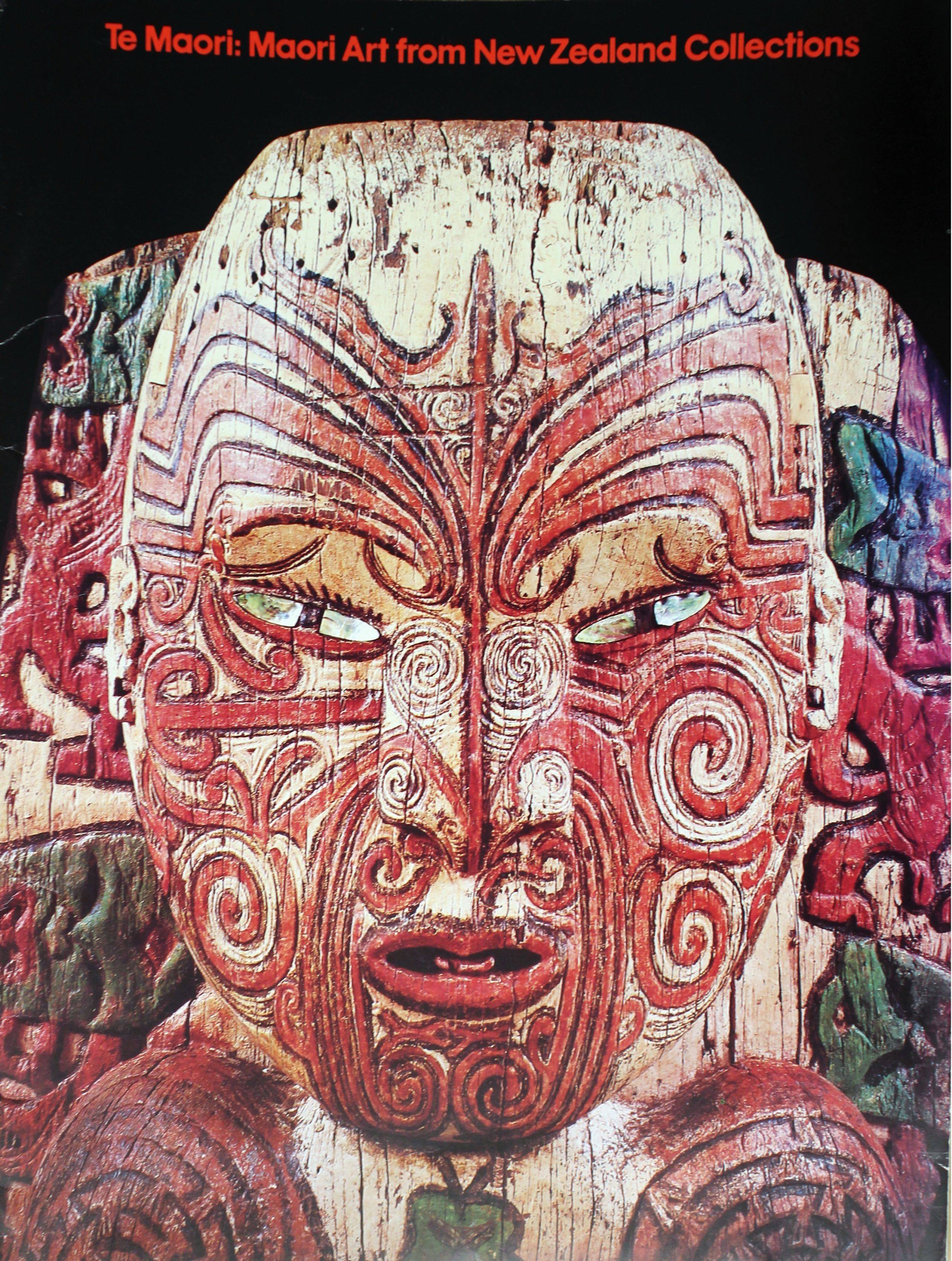

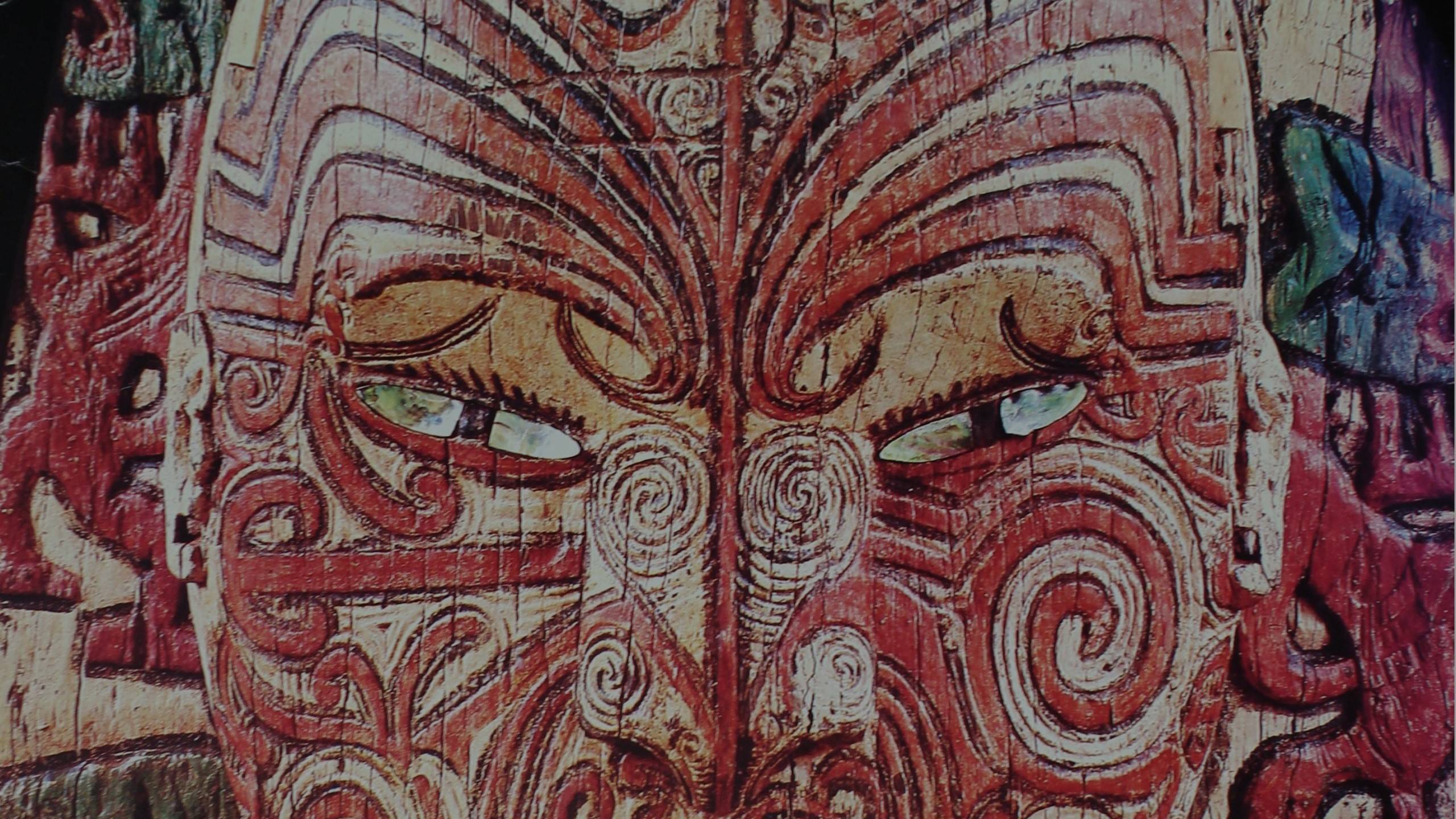

Image above: Te Māori Exhibition brochure cover featuring the head from the gatewayto Pukeroa Pā. Courtesy Archives NZ under Creative Commons Licence 2.0

At daybreak on 10 September 1984, five elder Māori women, positioned in sentinel formation on the steps of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, split the dawn air with wailing karanga, or spiritual calls of welcome.

Two Māori warriors, armed with traditional weapons, or taiaha, head a procession of distinguished New Zealand Kaumātua, or elders, toward the steps.

Taranaki Kaumātua, Sonny Waru, leads the way with his carved cane, or tokotoko, chanting traditional incantations announcing to the museum, Manhattan and the world that something special is about to happen.

Immediately behind, other elders versed in the traditional chants of their own tribal regions, are poised, ready to add their spiritual voices in support of Kaumātua Waru.

Following the Kaumātua group a large delegation of excited supporters, who have travelled from New Zealand for the opening, are about to play their part in the Te Māori exhibition.

Dr Kara Puketapu, former secretary of Māori Affairs and one of the main organisers of the event, remembers the ”awesome impact” New Zealand’s Māori culture made on a land and people on the other side of the world.

“Getting the treasures to the United States required 10 years of delicate negotiations. Indeed, the Wall Street Journal would later compare this feat alone to “persuading the Pope to let Bernini’s Baldachino out of St Peters”. Dr Kara Puketapu

Years of planning and determination have gone into this moment. Ascending the steps, the company hongi and touch noses with the American hosts before entering the second floor of the venerable New York institution.

Inside, the first group of visitors— whose number will swell to more than 600,000 in the months ahead — pass through the dramatic Pukeroa Gateway, which depicts a warrior ancestor known as Tūtanekai. They pause to acknowledge the Te Potaka storehouse lintel that illustrates the ancient story of Tinirau and his pet whale, Tūtunui.

Elsewhere are wood and stone sculptures. A panel in the centre aisle includes carvings from different iwi and tribes arranged as one might encounter them on a marae. On the wall hang depictions of ancestors carved atop each other’s shoulders.

In all, 174 pieces from various tribal collections were displayed, mostly arranged in chronological order up until the late 19th century.

Te Māori: Māori Art from New Zealand Collections is now open for cultural business.

The point will be underscored again the next day when the New York Times leads its front page with news of the event — a proclamation that spurs more than a thousand people to show up that night to see the same Māori cultural group perform at the American Museum of Natural History.

Te Māori is a first for America — but it’s a first for New Zealand as well — and a diplomatic first for New Zealand.

Image 1: Kara Puketapu, Managing Director of Maori International, on cover of Tu Tangata magazine published by the Department of Maori Affairs 1984. Courtesy Te Ara/ Te Puni Kōkiri.

Image 2:Installation of Te Māori exhibition at the National Museum, Wellington 1986. Courtesy Te Papa Tongarewa.

Blockbuster

Sir Pita Sharples was one of the leading warriors that morning in New York. The former minister of Māori Affairs describes that moment as the start of “a great awakening”.

Even by New York’s supersonically busy standards, “we are talking about what was a major production,” he says.

If the exhibition was a blockbuster on the stateside art circuit, it was just as huge in the making.

For the first time, as Sir Pita and others describe it, museums, ministries and management groups — in New Zealand and around the world — were engaging with Māori in a meaningful way on the planning, display and interpretation of their taonga.

By the time Te Māori finished its stateside run in Chicago the following year, more than 621,000 visitors had flocked to see it.

Image above: Opening of Te Māori Exhibition, New York, 10th October 1984. Credit Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Historical journey

The groundwork went back to 1972 when the Metropolitan and the de Young Museums first approached the government of New Zealand to discuss a major stateside exhibition of Māori art. The proposal found a supporter in the prime minister, Norman Kirk, on whose watch a basic list of 200 potential works was drawn up.

In order to distinguish the objects from those already on display in various American venues, it was decided that the emphasis would be on works dating only up to 1880.

Mr Kirk’s unexpected death in office and the oil-related financial crisis of the mid 1970s saw the initiative put on political hold for a while. But cultural enthusiasm gathered pace.

“There was a Māori art movement — a renaissance — going on long before Te Māori of course, going back to at least the late 1950s,” notes Darcy Nicholas, a Wellington-based senior executive, artist and curator of exhibitions who attended the New York exhibition as part of his Fulbright Scholar Award.

In 1979, the first of several planning meetings were held in New York involving some of these curators, representatives of the QEll Arts Council (now Creative New Zealand) and the old Department of Māori Affairs (now Te Puni Kōkiri), and their various American counterparts.

“But don’t forget there was a lot else besides going on in Māoridom at that point,” Dr Puketapu says.

In particular, he points out, a major hui, in 1981 emphasised “how frightened we were of losing our language”.

The idea of mounting a major international arts offensive as a way to help boost a much-needed awareness of Te Reo Māori was one of the key suggestions put forward to help turn the tide.

In 1982, with the support of then prime minister Sir Robert Muldoon, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs organised another hui bringing together iwi leaders and their various counterparts from the relevant ministries.

“It was a time of outreach, of progression,” Piri Sciascia, an official with the QEll Arts Council at the time, says, “not least the way it forced officials with often highly different agendas to work together.”

The foreign ministry was a case in point.

Officials would come to meetings not so much with different priorities as different agendas, Mr Sciascia remembers. It was “interesting” to see how these disagreements were ironed out, he says.

One such divergence opened up on the issue of ownership. Who could be said to “own” particular works in the standard commercial sense when the works represented a culture in which the word has a significantly different meaning? In the end, after a long weekend of haggling, it was agreed to change the wording to “cultural ownership”.

Agreements also had to be forged on how the government of New Zealand would act as the agent responsible for the practical arrangements.

A second set of agreements covering copyright was also required, including the prevention of images of the taonga being used in the wrong commercial context.

Copyright agreements needed to be signed and then, finally, a memorandum of understanding between the government of New Zealand and the American side reflecting all the other agreements and covering indemnification and first-risk insurance. This was finally signed off in 1984.

And even as many Māori came to embrace the international opportunity now afforded them, they continued to hold many debates among themselves about the propriety of sending ancestral spirits into the world of skyscrapers.

Vitality, verve and distinction

All was far from quiet on the diplomatic front, too. In the lead-up to Te Māori, a battery of telexes, cables and rotary-dial telephones were put to full use in the Ministry’s work with offices across the United States.

A number of New Zealand diplomats including Mattie Wall, Win Cochrane, Erima Henare and Hekia Parata were tasked with representing Te Māori on the ground.

Witi Ihimaera, a diplomat and well-known New Zealand author said, “Te Māori provided a unique waka, enabling New Zealand not just [to] showcase Māori taonga but also as leverage to maintain our trade, business, cultural and other relationships.”

In New Zealand, the Ministry worked alongside local iwi to facilitate contact with American exhibitors and representatives of the show’s major corporate sponsor, Mobil.

According to Dr Puketapu, one of the thorny issues was between the Americans — who had their own views of what attendees would enjoy seeing — and local Māori, who also had their own views on what they wanted to have displayed.

“The negotiations were sometimes intense,” he says with a rueful chuckle.

Hekia Parata, a young diplomat who would go on to become a cabinet minister in the last National-led government, enjoyed a bird’s eye view of the process.

1983, Ms Parata had only been with the Ministry for a year, yet she felt sufficiently emboldened to ask the Secretary, Merv Norrish “to consider whether it would be sensible for me to be sent overseas earlier in order to help out. Mr Norrish, bless him, agreed.”

She saw the exhibition as a golden opportunity to bring together the aesthetics of her upbringing with her diplomatic vision for New Zealand as a distinctly South Pacific nation.

“I was born and bought up in Ruatoria and I grew up sleeping in our meeting houses and eating in our dining areas, which is where I first saw many of these works,” Ms Parata says.

“I had never seen them as art as such, but… well, as my mother used to say when we stayed overnight in a meeting house, I saw them as sleeping at the feet of my ancestors. They were just there.

“So it wasn’t until this exhibition that I saw them, in museum-quality walling and museum-quality lighting and protection, as the most profoundly moving art. And we were all so proud. It was a first for New Zealand having Māori presenting their artwork, presenting it so well and, as we know, presenting it to stunning international acclaim. The whole thing had verve, vitality and distinction. It was a quantum leap forward for the whole country ultimately."

As the New York Times put it,the exhibition spoke to the world about “a race of master builders who gave to what we now call New Zealand a dignity that has certainly not been surpassed by anything the white man bought to the area'. The works reveal a “sure sense of scale and a regard for fine workmanship that will make this show a go-to again and again.”

Te Māori not only established Māori art on the global world stage but also provided an opportunity for indigenous artists to compare art forms and creation stories between Māori and the Iroquois or Haudenosaunee peoples.

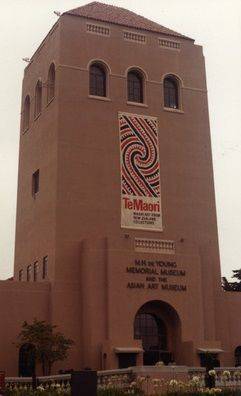

Image 1: Te Māori exhibition banner hanging from M.H. De Young Memorial Museum and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco 1985. Courtesy Auckland Museum under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Image 2: Installation of Te Māori exhibition at the National Museum, Wellington 1986. Courtesy Te Papa Tongarewa.

The great awakening

It all came back on that first morning in New York, Sir Pita says today of the “great awakening”. Sir Pita believes the exhibition not only awoke the American art world but the wider New Zealand culture.

“Te Māori put our art and culture and history and language on the world map,” he says. “It did such a good job that it put these things, finally, on New Zealand’s map, too. I mean, this was our whole life. We knew the whakapapa of all of these articles, who they came down from and how they were related. And then, suddenly, all over New Zealand there was all this newfound enthusiasm."

“When we came back, I was sort of thinking, You buggers. You’ve grown up amid this and ignored it. Now America recognises it and you’re jumping on the bandwagon. I was pretty, um … well, a bit hurt, but you know, that was a phase I went through.”

Not that Sir Pita is complaining about the tangible benefits he believes it delivered: newfound international respect, widespread domestic admiration and, most importantly for him, a much-needed boost in the drive to revitalise the Māori language.

Thirty-four years on, Te Māori is widely acclaimed as an exhibition that changed the way that museums and art galleries interpret and manage taonga Māori. The automatic acknowledgement that there is a living cultural dimension to Māori artifacts, for instance, marks a significant shift from the earlier time.

For the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, it underscored the need for presenting a bi-cultural face to the world, of the need for more Māori in overseas posts and the pleasure of the special relationships it fostered between New Zealand and the people of St Louis, San Francisco, Chicago and of course New York.

Today, the Ministry works harder to recruit Māori, and its Māori dimension overall is, as Ms Parata puts it, “less an add-on and more a central component” in 2018.

Erina Okeroa, a current staff member recalls that her kuia, Ngāhina Okeroa (Taranaki/Te Ati Awa kuia “Auntie Ina”), travelled to New York as one of the group’s kaumātua. “Her presence in New York wove a lasting connection between our whanau and Te Māori, both today and into the future. We remain incredibly proud.”

For Mr Nicholas, the arts curator, the smaller details of what remain are just as vivid.

“As everyone knows, New York City doesn’t stop for anyone — it’s a 24-hour-a-day deal. But it did stop, just this once, when Te Māori arrived. I remember the massive traffic jam, and the buzz it caused around the city at all levels."

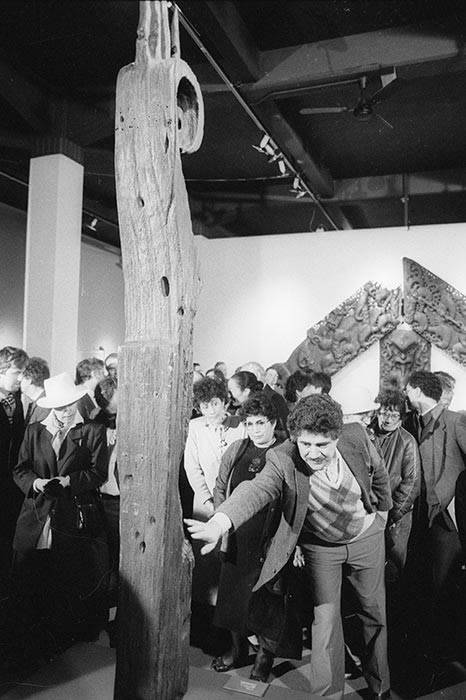

Image 1: Diplomat Tia Barrett of Ngāti Maniapoto touches Uenuku, a carved taonga (treasure) and tupuna (ancestor) of the Tainui tribes during Te Maori exhibition at Dominion Museum, Wellington, 1986. Credit: Alexander Turnbull Library, Dominion Post Collection (PAColl-7327) Reference: EP/1986/4000.

Image 2: Ngāhina Okeroa at opening of Te Māori Exhibition, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art 10 September 1984. From“Te Māori – A Celebration of the People and their Art”. Courtesy Getty/TVNZ

Image 3: Te Māori Exhibition brochure cover featuring the head from the gateway to Pukeroa Pā. Courtesy Archives NZ under Creative Commons Licence 2.0