Supply Chains:

On this page

Summary

- The twelve-day conflict between Israel and Iran was a dramatic and concerning development in the Middle East. The ceasefire between Israel and Iran is holding and risk of a deepening conflict appears to have abated.

- An escalating conflict between Israel and Iran would have major implications for global energy markets. Around 20% of the world’s oil trade transits the Strait of Hormuz, which was at risk of disruption in a prolonged or wider regional conflict.

- While New Zealand no longer imports crude oil directly from the Middle East, a surge in the global oil prices would still push the price of fuel and inflation higher. Increasing fuel prices don’t just show up at the pump but pervade the economy.

- Rising energy costs would weigh on consumer spending, economic activity, and may force the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to hike interest rates in response. Higher interest rates would lift debt servicing costs and further weigh on activity and employment.

- An oil price shock would also weigh on global economic growth, weakening general demand for New Zealand’s exports.

- A broadening regional conflict could also bring about market-access issues for New Zealand’s exports to fast-growing Middle Eastern markets, and lower returns for some exporters. New Zealand’s main commodity exports to the Middle East rely on open sea lanes including unimpeded access through the Strait of Hormuz. Taken together, Gulf Cooperation Council countries represent New Zealand’s sixth largest export market.

- Elevated economic uncertainty generated by major geopolitical events can sap consumer and business confidence, which in turn can hold back long-term decisions, such as investment.

- The New Zealand economy is also exposed to global financial market fluctuations. Commodity-based currencies, such as the New Zealand dollar, tend to depreciate during times of adverse global events. A weaker currency would exacerbate the inflationary impact of a deepening Middle East crisis, as it would push up the prices of imported goods and services.

Report

The twelve-day conflict between Israel and Iran was a dramatic escalation in events in the Middle East. The ceasefire between Israel and Iran is holding and risk of a deepening conflict appears to have abated, but some risk of further conflict remains. This report examines the exposure of New Zealand’s economy from a deepening crisis involving Iran and Israel. The Middle East is a critical source of energy, with its vast reserves and commercial extraction of hydrocarbons. The Middle East is also a growing export market for New Zealand, which is set to expand further when both the NZ-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and NZ-United Arab Emirates (UAE) free trade agreements come into force.

A major geopolitical event, such as an escalating or wider regional conflict in the Middle East, would transmit to the New Zealand economy through several channels. The dominant channels include global supply chain disruptions, market access issues for New Zealand’s exports, heightened economic uncertainty, and financial markets. These transmission channels are discussed in more detail below.

Prolonged disruption in the Strait of Hormuz would wreak havoc in global energy markets and supply chains

The Strait of Hormuz is a key vulnerability of global energy supply chains in the Middle East. The waterway, which separates the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, is a crucial transit route for global energy trade from major oil and gas fields in the region to markets abroad. During the conflict with Israel, Iran’s parliament approved a motion to close the Strait, although this has not been implemented.

Around 20% of global oil transits the Strait from major Middle Eastern producers, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Iraq, and Qatar. Therefore, disruption to supply in the Persian Gulf has meaningful implications for global energy supply and prices.

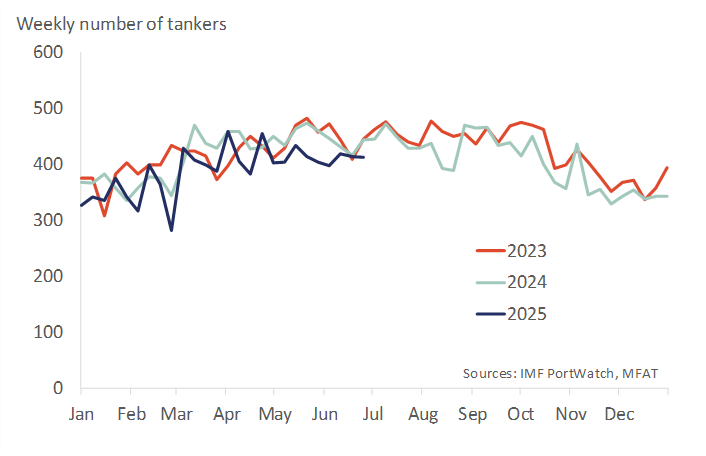

Oil prices were buffeted around by the rapidly evolving events in June as markets assessed the risk to future global supply, despite maritime trade able to transit the waterway unimpeded – albeit 7% down on 2024 (Figure 1). For instance, the spot price for Dubai crude oil reached a peak daily closing price of just under USD75/barrel on 18 June, up 17.5% from the price recorded at the start of June. Dubai spot was trading around USD65/barrel by the end of the month following the announcement of a ceasefire between Israel and Iran. Similarly, the West Texas Intermediate price hit a daily closing high of USD74/barrel in mid-June before diving to circa USD65/barrel at the end of June.

Figure 1: Transits of tanker vessels through the Strait of Hormuz

Some oil producers in the Gulf have alternative routes to export product and avoid the Strait. For instance, Saudi Arabia can pipe oil away from Persian Gulf terminals to export terminals on the Red Sea. However, given the sheer volume of oil and gas that transits the Strait of Hormuz, only a limited volume could use alternative routes out of the Gulf.

New Zealand no longer imports oil from the Middle East but is still highly exposed to events in the region

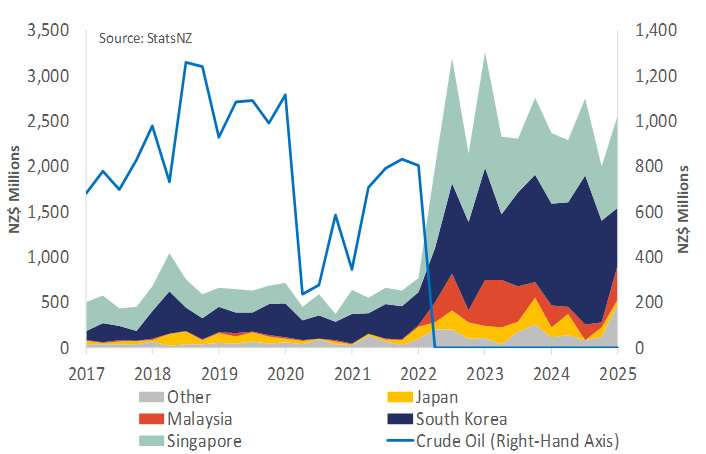

New Zealand no longer imports crude oil in any meaningful quantities following the closure of the Marsden Point oil refinery in 2022. The site is now used as an import terminal for refined petroleum. Since 2022, most refined petroleum product imports are sourced from a handful of Asian countries. These include Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia, and Japan (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Refined petroleum imports into New Zealand by source countries

However, the end of oil refining in New Zealand does not mean New Zealand is no longer exposed to Middle Eastern energy markets. Having few large operational oil fields, North and Southeast Asian refineries are major importers of crude oil from Persian Gulf counties. In 2024 New Zealand’s top four source countries for petroleum sourced almost 80% of crude oil imports from countries surrounding the Persian Gulf. In the event of disruption of Middle Eastern supply, Asian refineries would be forced to source crude product from elsewhere, pushing up the global price for oil.

Disruption to global energy supply is likely to be inflationary and weigh on New Zealand’s economic growth

Some commodity market analysts had picked that a closure of the Strait of Hormuz could see the oil prices surge close to USD100/barrel from current prices. In the present economic environment, such a large jump in oil prices would be a significant supply-side shock for the global economy and would drive-up imported inflation for many economies, including New Zealand.

The rising cost of fuel would likely be a drag on household consumption at a time of resurgent food price inflation. However, rising petrol prices don’t just show up at the petrol pump, they also pervade the economy via rising business costs for services such as transportation and key imported inputs such as fertiliser. And higher business costs are likely to be passed onto customers downstream.

While central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), tend to look through temporary oil price shocks when making monetary policy decisions, an oil price shock that has lingering effects may force the RBNZ to raise interest rates. Higher interest rates would add to debt servicing costs for New Zealand households and businesses and further weigh down economic activity.

More broadly, many of New Zealand’s trading partners are net oil importers too and would face similar inflation pressure and slowing economic activity. Weaker trading partner growth would reduce demand for New Zealand’s exports.

A worsening or wider regional conflict in the Middle East would likely put access to a fast-growing market for New Zealand exporters at risk

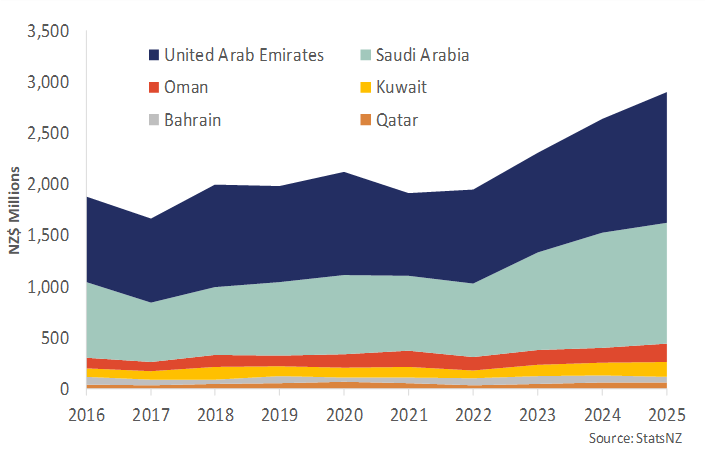

Since 2022, New Zealand’s exports to GCC members have grown rapidly (Figure 3). In the year to March 2025 exports to the GCC were valued at almost NZD3bn, almost 50% higher than the same period in 2022. If GCC member countries were treated as a single country, it would be New Zealand’s sixth largest export market.

Figure 3: New Zealand’s exports to GCC member countries

New Zealand’s exports to GCC countries are highly concentrated, with 85% of exports destined for the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and 73% of exports consisting of dairy and meat products. Nevertheless, GCC countries represent a major future export growth opportunity as they invest heavily to transition away from their reliance on fossil fuels. An opportunity enhanced once the NZ-GCC and NZ-UAE free trade agreements come into force.

New Zealand’s main commodity exports to the Middle East rely on open sea lanes including unimpeded access through the Strait of Hormuz. Limited access to Middle Eastern markets would likely hit some major exporters in the pocket requiring product to be diverted to other markets at a discount.

Again, there is the possibility of exporters using alternative routes that avoid the Strait of Hormuz. These include overland routes from ports in Oman or Saudi Arabian ports on the Red Sea. Access to major UAE ports is likely to prove far more difficult as the UAE relies heavily on open access to the Strait of Hormuz. However, alternative routes may not have the capacity to service the required volume of trade, given all exporting countries to the Persian Gulf would look to use them. Moreover, major shipping companies continue to avoid sailing the Red Sea, following attacks by Houthi rebels from Yemen. Alternative transport routes are likely to come with higher transportation costs, which would eat into exporters’ margins.

Economic uncertainty can be heightened during geopolitical events, which can sap confidence and growth

Uncertainty thrown up by a major geopolitical event, such as conflict in the Middle East, can also harm the New Zealand economy. Uncertainty undermines business and consumer confidence and can hold back decisions that have long-term consequences, such as investment and hiring. For example, the uncertainty thrown up by conflict in the Middle East may deter New Zealand exporters from exploring lucrative opportunities in the region.

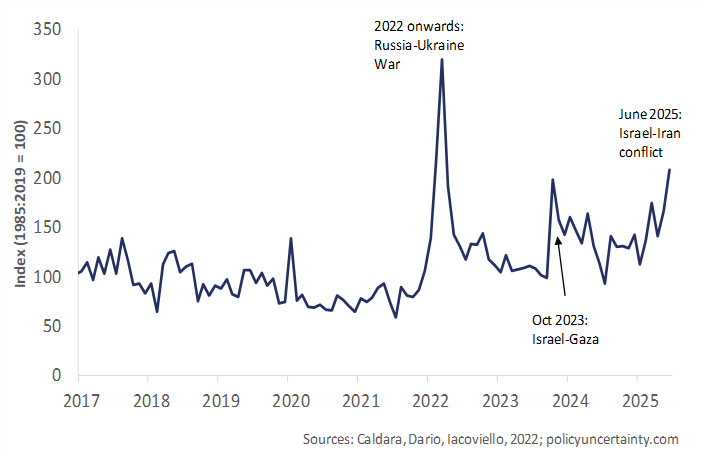

In the last five years, measures of geopolitical risk have been rising because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and conflict in the Middle East that began in October 2023. Geopolitical risk also jumped higher in June as a result of the Israel and Iran conflict (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Geopolitical Risk Index (1985:2019 = 100)

The New Zealand dollar is at risk from geopolitical events

Financial markets are another key channel that geopolitical events can transmit through to the New Zealand economy. Commodity-based currencies like the New Zealand dollar tend to depreciate during times of heighted economic uncertainty, as global investment flows tend to seek out safe-haven currencies such as the US dollar or in recent times the Euro. A weaker New Zealand dollar would contribute to rising imported inflation, as all imports would cost more in New Zealand dollar terms. However, the corollary would be the support it would provide to New Zealand exporters’ incomes given much of our exports are priced in foreign currency, particularly the US dollar.

Risks on the New Zealand economy from a deepening conflict look to be easing for now

The prospect of regional escalation in the Middle East appears to be abating. A ceasefire between Israel and Iran is holding and negotiations continue towards a ceasefire in Gaza. As a result, risks to the New Zealand economy from these events are also easing.

Nevertheless, New Zealand’s geographic isolation does not insulate the economy from major global events, such as escalating conflict in the Middle East. As a small trading nation New Zealand relies on open transport routes, such as international shipping lanes, to allow the free flow of goods and people around the world. There are multiple channels that transmit the effects of geopolitical crises. And not all are directly trade related. These include, global supply chain disruption, market access issues for our exports, heightened economic uncertainty, and financial market developments.

More reports

View full list of market reports(external link)

If you would like to request a topic for reporting please email exports@mfat.net

Sign up for email alerts

To get email alerts when new reports are published, go to our subscription page(external link)

Learn more about exporting to this market

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise’s comprehensive market guides(external link) export regulations, business culture, market-entry strategies and more.

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.

Copyright

Crown copyright ©. Website copyright statement is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence(external link). In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to the Crown and abide by the other licence terms.