Supply Chains, Primary Products, Services:

On this page

Summary

2023 Full year data

- China’s official GDP growth for 2023 was 5.2%, nudging past the annual growth target of 5% set by the Chinese Government. The figure was announced by Chinese Premier Li Qiang at the World Economic Forum in Davos on 16 January.

- The 5.2% figure marks a rebound from the 3% GDP growth rate of 2022, but is less than pre-pandemic growth rates (2015-2019 growth rates were north of 6%). The continued weakness of China’s property sector and lower-than-anticipated consumer spending were major headwinds in 2023.

- China’s population shrank for the second consecutive year, falling by 2.08 million (0.15% year-on-year) to 1.409 billion in 2023. The trend was driven by the falling national birth rate and a higher death rate.

2023 Fourth Quarter

- China’s economy grew by 2% (yoy) in Q4 (and 1% quarter-on-quarter), although from a low base in 2022. Underneath the headline growth figure, economic indicators were mixed. Retail sales and measures of industrial activity surpassed expectations in October, but missed market expectations in November and December. The property sector sank further with low uptake in household borrowing and month-on-month drops in new house sales. However, exports grew by 2.3% yoy in December.

- China’s biggest annual e-commerce sales festival ‘Singles Day’ took place on 11 November and was viewed as an opportunity to spur household consumption. However, independent data suggests there was only a 2% yoy increase in sales (less than the 2.9% yoy growth notched in 2022). The weak sales data comes despite hefty discounts offered by major retailers. China’s major e-commerce platforms have not released headline sales figures.

- Measures of selling price in both manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors contracted in December. Analysts contend businesses were cutting prices in response to weak demand. Measures of new orders were also down in December.

Government response

- In late-2023 the Chinese government shifted to a more proactive stance on fiscal stimulus to support economic activity. The Chinese government approved RMB 1 trillion (NZD 228 billion) in sovereign bonds to finance infrastructure projects, among other measures. Issuing extra bonds of this magnitude has only occurred in 1998 and 2000, (the latter during the Asian financial crisis).

- On 15 January China’s central bank kept its main policy interest rate unchanged for the fifth consecutive month, and signalled to the banking sector the need to improve lending to property developers and private businesses.

- After a difficult 2023, Chinese stock markets tumbled in the first days of trading in 2024 and have declined further over January. In response, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) announced a 0.5% cut to the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR),[1] on 24 January, which would inject 1 trillion RMB (NZD 228 billion) in cash to the banking sector. This would increase commercial banks’ ability to lend and improve bank profitability. The move is viewed as strong signal of support for the economy.

- One year since China dropped all its pandemic restrictions, the economic recovery is “still at a critical stage” according to President Xi Jinping. While economic growth has recovered from the COVID-low of 2022, government support will be required going into 2024.

Looking ahead: Prospects for the Year of the Dragon

- Current forecasts for China GDP growth in 2024 average around 4.6%. Economist stress the importance of China addressing challenges to growth, in particular stabilising the property market and implementing policy support to drive household consumption.

- Market sentiment is moderated by the persistent downside risks weighing on China’s economy: deflationary pressure; the property market; local government debt; youth unemployment; households’ reluctance to spend; and China’s falling and aging population.

New Zealand-China trade

- China remains Aotearoa New Zealand’s top trading partner, with two-way goods and services trade totalling NZ$38.67 billion in the year ending September 2023[2].

- Despite ongoing uncertainty over China’s immediate economic trajectory, the factors that have made China New Zealand’s largest export market remain fundamentally strong: a large and still growing middle class with an appetite for high quality products and services.

Report

Annual growth target attained

China’s official GDP growth for 2023 was 5.2%, surpassing the annual growth target of “around 5%” set by Chinese Government in early 2023. This was a rebound from the 3% GDP growth rate of 2022, but remains slower than pre-pandemic growth rates (north of 6%).

The annual growth figure was announced by Chinese Premier Li Qiang at the World Economic Forum in Davos on 16 January, who emphasised “the Chinese economy can handle ups and downs in its performance. The overall trend of long-term performance will not change”. Expressing optimism in the Chinese market, Li stressed “choosing the Chinese market is not a risk, but an opportunity. So we embrace investments across businesses of all countries with open arms.” These comments are consistent with efforts by Chinese provincial and city-level governments to attract foreign investment.

On 17 January China’s National Bureau of Statistics revealed the country’s population shrank for a second consecutive year, falling by 2.08 million (0.15% yoy) to 1.409 billion in 2023. The trend was driven by the falling national birth rate and a larger death rate (9 million births to 11 million deaths).

China also published the youth unemployment rate for December – the first time it has done so since June 2023. The December youth unemployment rate of 14.9% was an improvement from the last reading in June 2023 at 21.3% (the highest monthly data point since the measure began). Notably, the calculation method for the youth unemployment rate has changed: it only includes 16-24 year olds; 25-29 year olds are split into a separate bracket (which had a 6.1% unemployment rate in December); and excludes students searching for part-time jobs or post-graduate work. Commentators highlight that the new methodology does not reflect the millions of students continuing their tuition due to poor employment prospects.

In 2023 electric vehicles were a bright spot for the Chinese economy, with sales in China increasing by 35.7% yoy to reach 9.58 million and accounted for 34.1% of all vehicles sold. In 2023 China became the world’s largest exporter of all automobiles for the first time. China exported 4.91 million vehicles, of which 25% or 1.2 million, were electric vehicles. However, there have been challenges for the sector too. China’s increased production and international market presence has caught the eye of EU regulators, who in September launched an investigation into China’s state support for makers of electric vehicles. Finding are expected to be released later in 2024.

Patchy results in Q4

There was some momentum in the economy over October and November, but this was from a relatively weak level when comparing the same period in 2022. Retail sales grew 7.6% yoy and 10.1% yoy respectively over October and November, while industrial activity grew 4.6% yoy and 6.6% yoy respectively. Industrial activity was bolstered by strong growth in renewables, with solar batteries and New Energy Vehicles (NEVs), increasing 62.8% and 28% respectively in October. Automobiles continue to be a strong performer for both industrial activity (20.7% yoy growth in production in November) and retail (14.7% yoy increase in sales in November) There was a slight increase in exports in November (1.7% yoy) after a fall in October (-3.1% yoy).

December’s results were mixed. An area of strength was growth in exports, up for a second consecutive month, rising 2.8% yoy in December to a total value of 218 billion RMB (NZD 50 billion), up by 3.8% yoy. Analysts see room for exports to lift further in 2024 if global inflation eases and foreign demand picks up. Imports also notched an increase, tracking up 1.6% to a total value of 163 billion RMB (NZD 37 billion).

There is anecdotal evidence that due to subdued demand from Europe and the U.S. and reduced commodity prices, some buyers are concluding supply contracts for 2024 with Chinese factories that are priced lower than 2023. This may help reduce price pressures in other countries (i.e. falling export prices of Chinese goods may see cheaper goods on the shelves of overseas markets).

However there’s less optimism for domestic demand. Measures of selling price in both manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors contracted in December, as did measures of new orders. Analysts contend businesses were cutting prices in response to weak domestic demand.

This lack of demand raises concerns that low inflation will persist. The official Consumer Price Index in November dropped by 0.5% yoy and month-on-month but recovered ground in December with a 0.1% increase month-on-month (0.3% decrease yoy). The risk of moving into a deflationary environment has been attributed to sluggish manufacturing growth, a pay down of debts rather than new investment, fierce competition in the automobile sector (especially among e-vehicle manufacturers) and falling food prices – e.g. pork prices were down by 31.8% yoy and 26.1% in November and December respectively[3].

Singles Day a barometer of consumer sentiment?

China’s annual 11.11 “Singles Day” on 11 November – the largest e-commerce sales event in China – was slated as an opportunity to spur consumption in Q4. China’s State Postal Bureau recorded 5.26 billion express delivery packages, up 23% yoy in the eleven days associated with the Singles Day sale. E-retail giants JD.com and Alibaba’s public statements spoke of high sales number for specific topics, but stopped short of publishing headline sales figures.

In lieu of this, third party data provider Syntun estimated that gross merchant value (GVM) across major Chinese e-commerce platforms rose 2.08% yoy to RMB 1.14 trillion yuan (NZD 259 billion) (NB: GVM is a measure of value of goods sold via customer-to-customer or e-commerce platforms). This year’s growth in GVM was less than the 2.9% Syntyn published last year. The lacklustre sales data comes despite hefty discounts offered by major retailers. Analysts concluded that Singles Day was no panacea for tepid domestic demand. Consumers have adopted a more rational and value driven approach to their purchases, with higher sales volumes not corresponding to a commensurate rise in sales value.

Property sector remains troubled

The property sector continues to act as a drag on China’s economy. To support the sector – that now represents roughly 30% of China’s annual GDP – the central bank cut interest rates in June and August to stimulate demand for mortgages. A revival in consumer demand did not eventuate. In November, property sales fell 10.3% yoy, after an 11% drop in October. In seasonally adjusted terms, sales amounted to about 60% of the average in 2019. Data on new home sales volume in December showed a 16% drop yoy.

The lack of confidence in the property sector is also limiting the finance made available to property developers by commercial banks. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has publically signalled its intention to improve private finance for property developers, and that it wants to see banks lending more to both developers and buyers. We have seen reports that banks have been privately instructed to ensure their lending to the property sector does not fall below the industry average, and lending to private developers and to buyers of non-state housing do not fall below the bank’s overall growth in lending. Moreover, PBOC is reported to be drafting a list of 50 developers who will be eligible for improved finance.

Analysts view this as a strong signal of support for the property sector. The improvement in cash flow may support some new construction and project completion, but analysts believe developers will more likely use this credit to pay down existing debt. This would lower overall financial risk in the sector, but would not create a flurry of new construction activity.

Debt relief for local government…

Another financial risk in the Chinese economy is local government debt. China’s central bank has allowed local governments to issue ‘refinancing bonds’. In practice, this means local governments can sell these bonds with the proceeds being used to pay off debt held in local government financial vehicle (LGFV) (where a lot of local government debt is held). This effectively shifts debt away from local government to central government. Guaranteeing this debt mitigates the risk of a provincial LGFV defaulting.

At the same time, fiscal restraint has also been exercised, with the trimming of some officials’ salaries by significant amounts in central and local government.

… and tangible policy support the private sector

On 27 November, China’s central bank and seven other agencies announced measures to support business activity through improving access to finance. Specific measures include: requiring banks to set annual targets for private sector support; regulators have signalled increased comfort with heightened risk; and policies to support capital markets to increase their contribution to private financing, including through cross-border investments.

The Central Bank announces fiscal stimulus to support growth momentum…

Against a backdrop of persistent downside risks, China has shifted to more proactive fiscal stimulus. At China’s Central Financial Work Conference between 30 and 31 October, People Bank of China’s Governor, Pan Gongsheng, stressed the need for the central bank “to create an enabling monetary and financial environment”.

In October China’s legislature approved RMB 1 trillion (NZD 228 billion) in sovereign bonds to finance infrastructure projects. Issuing extra bonds of this magnitude has only occurred in 1998 and 2000, (the latter during the Asian financial crisis). The newly issued bonds will support the stabilisation of the property sector, notably through the “three major projects”. This slogan refers to a city-level programme aimed at: 1) building more social and affordable housing; 2) renovating “urban villages”; and 3) improving infrastructure that can be used as emergency facilities during natural disasters.

In December a further RMB 350 billion (NZD 79 billion) was injected into policy banks [4] by the PBOC. Analysts suggest this will also support infrastructure development/construction through the “three major projects”. This will be an import tool for driving economic growth.

… while remaining cautious on monetary policy

However, the PBOC has remained cautious with its monetary policy. On 15 January it held the Medium-term Lending Facility (MLF) rate at 2.50% for a fifth consecutive month (the MLF is the main rate commercial banks use to set their own interest rates). Analysts suggest the decision to hold the MLF rate was motivated by concern around low bank profitability. Unprofitable banks increase risk in the broader financial system. So a cut to interest rate by the Central Bank would likely pressure banks to cut their own interest rates, reducing bank profitability.

Chinese stock markets hit five-year lows and elicits response from Central Bank

After a difficult 2023, Chinese stock markets tumbled in the first days of trading in 2024 and have declined further over January. China’s benchmark stock market, the CSI 300, has lost 9% in 2024 (falling 23% over the last 12 month), and is now entering its fourth year of declines. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index, which includes the shares of many big Chinese companies, has already fallen 12% this year, making it the worst-performing major stock index in Asia. Over a longer horizon, Bloomberg reports China and Hong Kong stock markets have lost USD 6.3 trillion (NZD 9.7 trillion) since their peak in 2021.

In response to the tumbling stocks, on 24 January the PBOC announced a 0.5% cut to the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) [1] that would take place on 5 February, which would inject 1 trillion RMB (NZD 228 billion) in cash to the banking sector. This would increase commercial banks’ ability to lend and improve bank profitability. While a cut to the RRR was anticipated by some analysts, this was earlier than expected. This loosening of monetary policy is viewed as strong signal of support for the economy amid the downturn in stocks.

It is also reported China is considering a 2 trillion RMB (NZD 450 billion) stock stabilisation fund. The fund would buy mainland China-listed shares through the Hong Kong stock exchange. In addition to the fund, authorities have reportedly earmarked another 300 billion RMB (NZD 68 billion) to invest in mainland Chinese shares. If the above measures do eventuate, analysts anticipate this to stem the speed of the stock market decline.

An economy in transition

China’s economic performance in 2023 was mixed. After a short burst of post-COVID economic recovery in Q1, the following quarter saw growth fall below expectations, while Q3 saw growth momentum stabilise and a patchy Q4 proved consolidating growth was not guaranteed. Throughout 2023 economists had repeatedly adjusted their growth forecasts to around 5%, and were mostly in line with China’s annual goal that was considered modest when set in March.

With double-digit growth no longer realistic, analysts view Chinese authorities as steering the economy toward a stable middle path: supporting sustainable demand-driven growth on one hand, while managing financial risks on the other. As China’s central bank governor, Pan Gongsheng, told investors in Hong Kong in November, “China is experiencing a transition in its economic model”.

Part of managing this financial risk is a re-sizing of the role of property in the economy. Data released on 17 January showed investment into real estate fell by 9.6% in 2023, while those into infrastructure and manufacturing rose by 5.9% and 6.5%, respectively. So it is evident an economic transition is under way, but a property market that shrinks too fast creates systemic financial risks (e.g. large property developers defaulting) and could further weaken already low consumer confidence. So how will China respond? Analysts contend there will be much of the same; a continuation of small incremental policy support.

Prospects for the Year of the Dragon

The Chinese government has placed much focus on the challenges facing its economy. President Xi Jinping is reported to have told a political meeting in December that, while China’s post-pandemic economic recovery was improving, the economy faced an adverse global environment and overlapping domestic cyclical and structural challenges: “At present, our country’s economic recovery is still at a critical stage”. While economic growth has recovered from the COVID-low of 2022, government support will be required to consolidate growth amid persistent headwinds.

In light of these challenges, the government has demonstrated willingness to respond. The issuance of refinancing bonds by local government and the haircuts to salaries and some public services will manage risk on the balance sheets of local government. Measures to improve financing to property developers will reduce risk of large developers defaulting on loan and worsening market sentiment. The responsiveness of the government to the stock market decline demonstrates a clear sensitivity to market sentiment. But these moves alone won’t help bring a turnaround in low consumption levels. Consumers appear to still be spending cautiously, with more focus on value and essential purchases.

Market observers are not convinced the government will implement policies to directly boost consumption. Observers emphasise that economic pessimism drives household saving – not spending – and so argue households need “cash in hand” to boost their confidence. However, the inflationary effect of cash stimulus in some Western economies during the pandemic has cooled enthusiasm for similar policies in China. Regardless of which policy approach China adopts, it will need to stimulate consumption not only to stimulate growth, but to dispel the current deflationary pressures that risks prices and wages falling. This in turn would make it harder for China to pay its debts. In short, the challenges in the year ahead remain significant.

With the above factors in mind, financial institutions and economists have forecasted GDP growth of around 4.2-4.9% in 2024 (averaging 4.6%). It remains to be seen if the “vigour of the flying dragon” – as channelled by Premier Li in Davos – will see the property market recover and give Chinese households the confidence to spend.

New Zealand China trade: Recent trends in key export sectors

NB: the most recent goods trade data available for New Zealand from Global Trade Atlas is to November 2023; for services trade and total trade the most recent data available from StatsNZ is to September 2023.

China’s economic transition is not entirely new, nor is it expected to alter the fundamentals that have made China the top export market for New Zealand companies. Those fundamentals include: a large, and still growing, middle class with an appetite for high quality, trusted goods and services; a demand/supply gap for the types of food and beverage products New Zealand excels at; and, significant scales of economy in China’s domestic logistics chains.

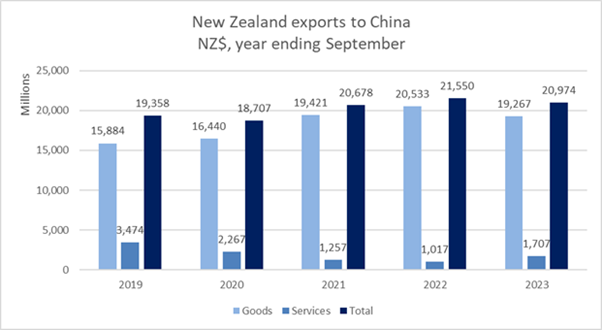

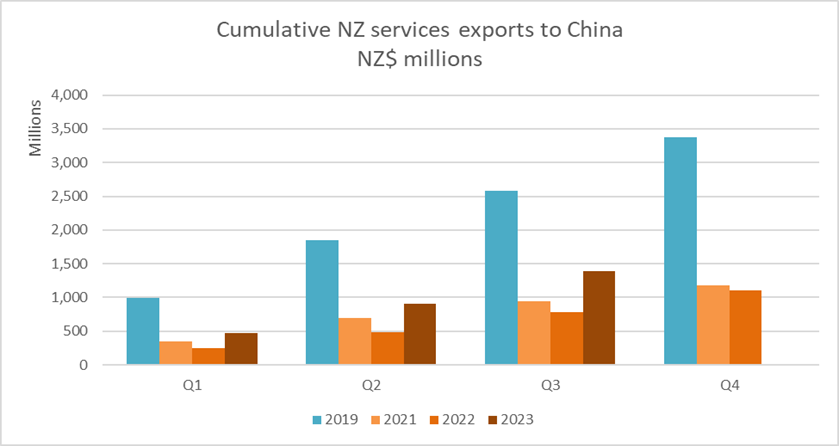

China remains Aotearoa New Zealand’s top trading partner, with two-way goods and services trade totalling NZ$38.67 billion in the year ending September 2023. While New Zealand’s goods exports to China have declined in the past 12 months compared to the two years prior, services exports have started to recover from their low point during the COVID pandemic.

The following sections of this report look at the performance of key sectors during the 11 months to November 2023 compared to previous years.

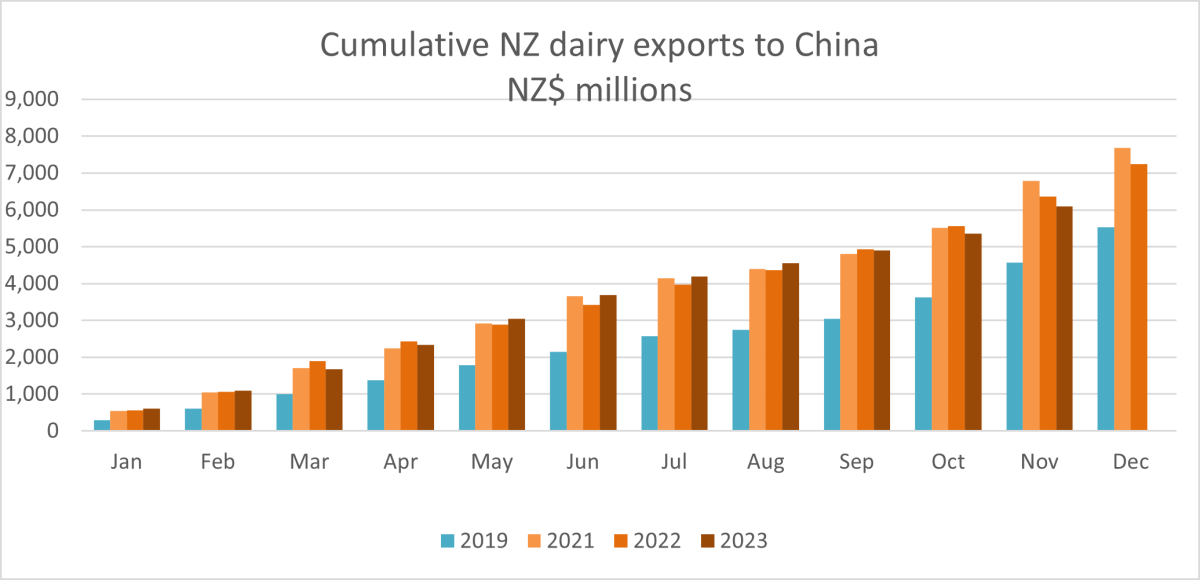

Dairy (excluding infant formula)

The value of New Zealand’s dairy exports to China in the first 11 months of 2023 totalled NZ$6.1 billion, down 4.1% on the equivalent period in 2022. Within the broad category of dairy, the performance of various product groups has been varied. Milk powder and butter are down compared with the same period a year ago (18% and 5% respectively), while liquid milk, cream, and cheese are up (9% and 41% respectively). Subdued demand in the China market has been driven by a degree of economic pessimism among consumers and strong domestic production. This in turn has put strong downward pressure on global dairy prices over the past 12 months. New Zealand dairy companies and their import partners received a boost on 1 January 2024, when all remaining tariffs on milk powders were removed by China under commitments made in the bilateral Free Trade Agreement.

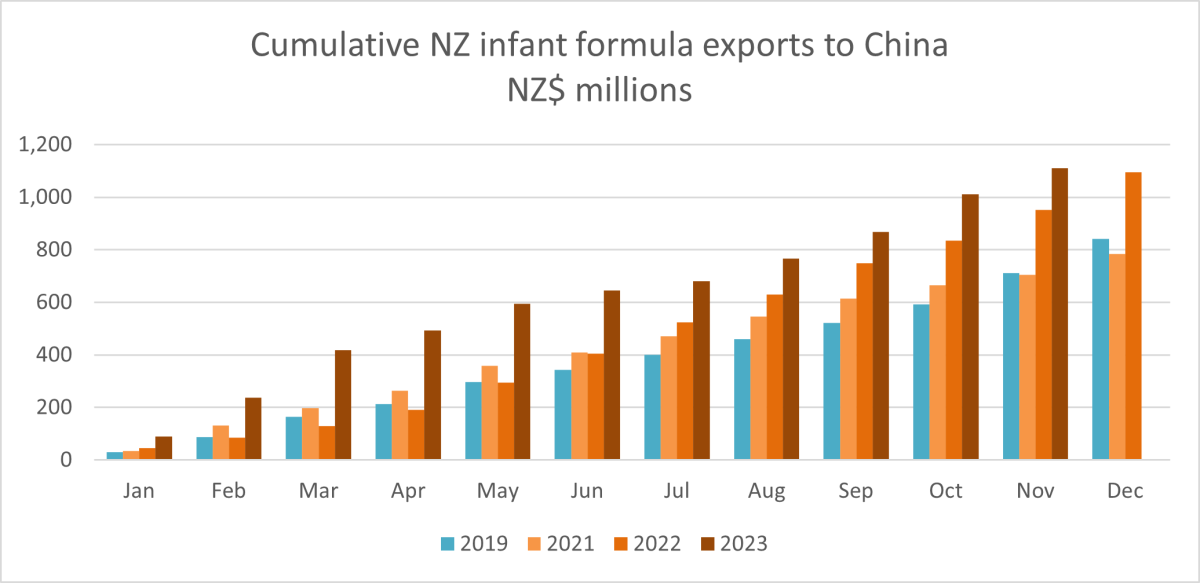

Infant formula

Infant formula has continued to perform strongly, year-on-year. In the 11 month period to November 2023, New Zealand’s infant formula exports to China reached NZ$1.1 billion, a 16% increase on the same 11 month period last year, driven by price gains. Infant formula is on target for a record export value this calendar year.

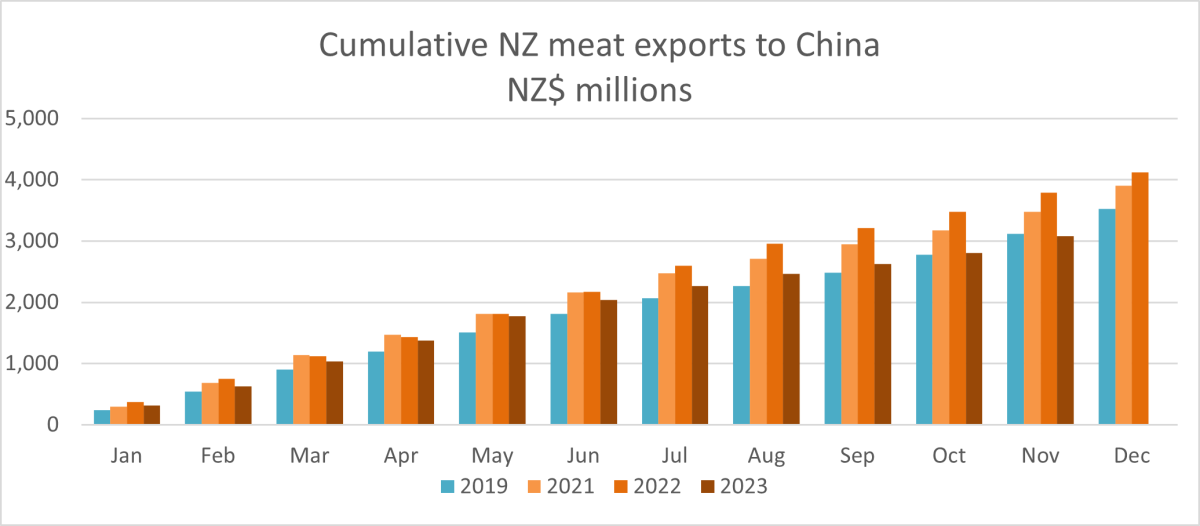

Meat

Meat exports to China in the 11 months to November 2023 were NZ$3 billion, down almost 20% on the year prior. This reflects both a decline in prices for beef and a decline in export volume and prices for sheep meat. The drop in prices in China is driven by tepid consumption, a high inventory of red meat in market and intensifying competition, particularly from Central and South American suppliers.

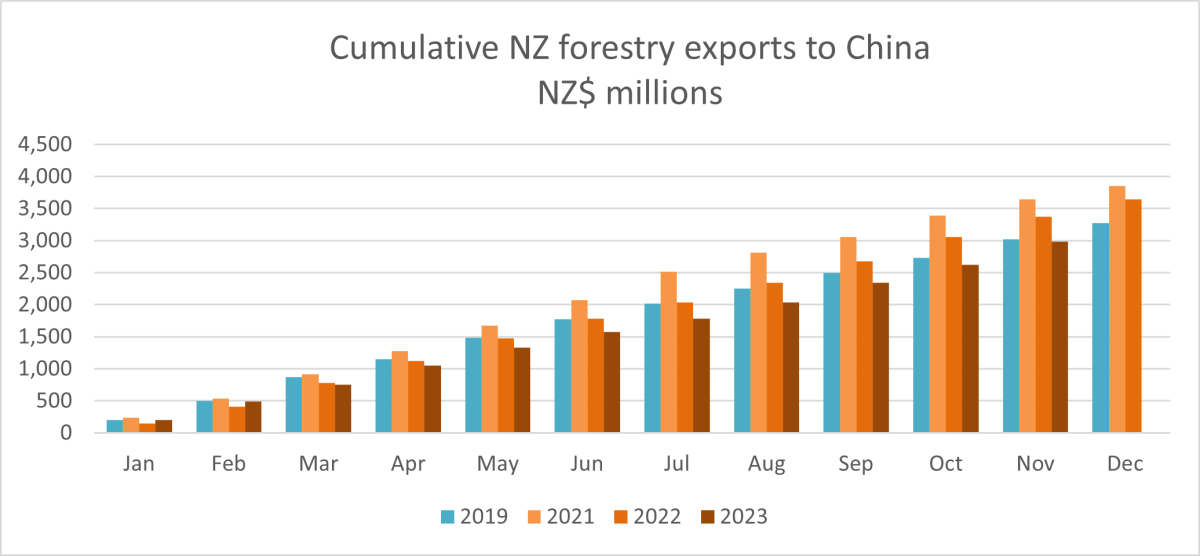

Forestry/wood

New Zealand’s forestry and wood product exports to China decreased by around 11% in the 11 months to November 2023, to NZ$3 billion, when compared with the same 11 month period a year prior. New Zealand’s trade in forestry and wood products is dominated by shipments of raw logs. The weakened demand for New Zealand logs and other wood products is largely a result of the continued downturn in China’s property sector. There is also strong demand for New Zealand product in other markets.

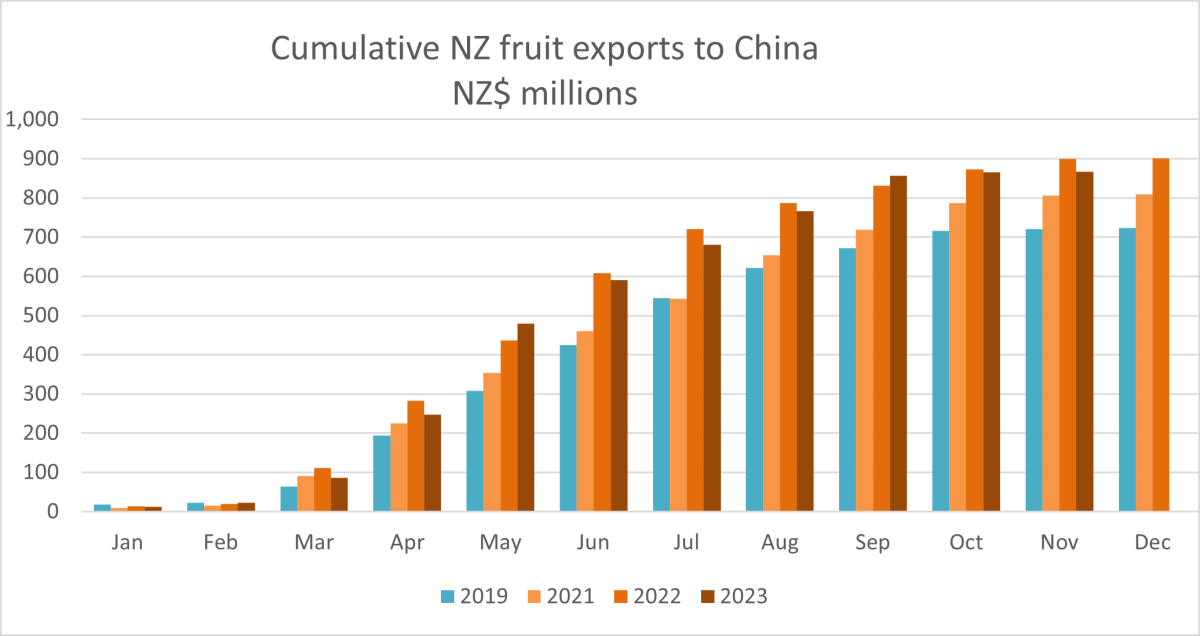

Fruit

New Zealand fruit exports to China totalled NZ$866 million in the 11 months to November 2023. New Zealand’s fruit export profile is dominated by kiwifruit which, despite a challenging growing season, maintained similar volumes into China as the year prior, and enjoyed a 4% increase in value. Apple exports were down 17% in the first 11 months of 2023. This is reflective of a wider drop in New Zealand apples export volumes to the lowest level seen since 2012 following damage to key growing areas by Cyclone Gabrielle in February 2023.

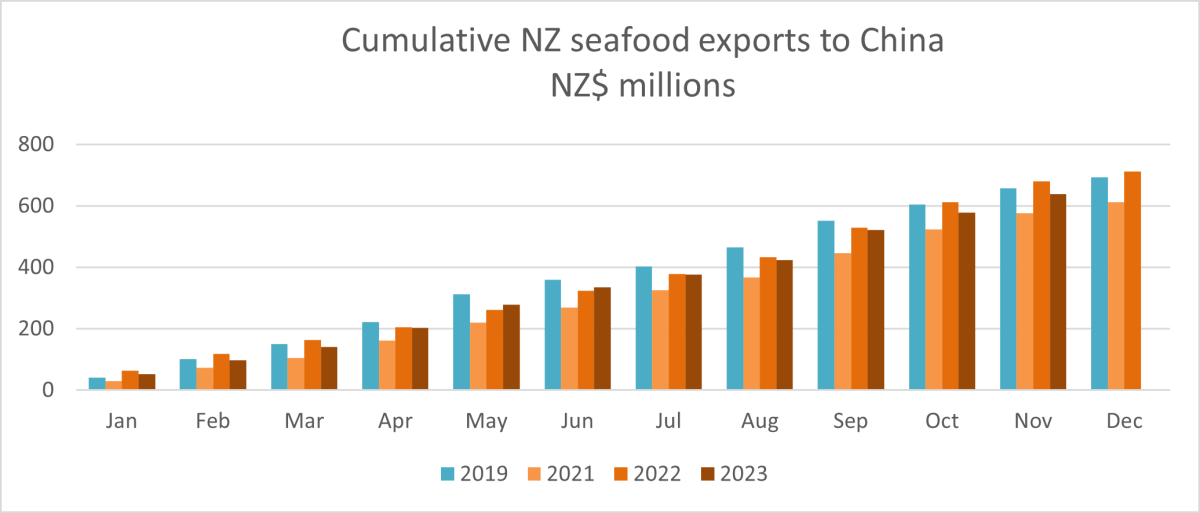

Seafood

Seafood exports to China were down 6% in the first 11 months to November 2023 compared with a year prior. New Zealand ranks 12th in terms of major source markets for China’s seafood imports. Market intelligence suggests that Chinese consumer confidence in both imported and domestic seafood products has been negatively affected by the Chinese government’s concern with the wastewater release from Fukushima, Japan. More generally, New Zealand’s seafood export volume globally has dropped as the industry undergoes a structural change moving from volume to more high value trade.

Wine

New Zealand wine exports to China totalled NZ$ 34 million in the 11 months to November 2023. This value is already greater than achieved in the full 2022 calendar year. China was the sixth most important destination for New Zealand wine in 2023, although less than 2% of New Zealand wine exports went to China. Of these wine exports to China, around 75% are white wine. Based on China’s import statistics, New Zealand wine accounted for 2.5% of all wine imported so far in 2023; France currently dominates China’s imported wine market, accounting for almost 50% of all imported wine in China. China remains a predominantly red wine market.

Services

1. Reserve Requirement Ratio is the percentage of a commercial bank's deposits that it must keep in cash as a reserve.

2. The most recent goods trade data available for New Zealand is to November 2023; for services trade and total trade the most recent data available is to September 2023.

3. Pork plays an outsized role in consumer price inflation due to its importance as a protein source to Chinese households. Pork prices have become more volatile in China since the outbreak of African Swine Fever in 2018 which saw a doubling of prices and a 20% drop in production.

4. Policy banks in China refers to the Agricultural Development Bank of China, China Development Bank and The Export-Import Bank of China. These institutions are responsible for financing economic and trade development, and state investment projects.

More reports

View full list of market reports(external link)

If you would like to request a topic for reporting please email exports@mfat.net

Sign up for email alerts

To get email alerts when new reports are published, go to our subscription page(external link)

Learn more about exporting to this market

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise’s comprehensive market guides(external link) export regulations, business culture, market-entry strategies and more.

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.